You Can Make It Happen

This article is adapted from a speech Jim Skaggs first delivered in 1999

It’s not what you are that holds you back, it’s what you think you are not.

Denis Waitley

As far back as I can remember, I have enjoyed a fundamental belief system that you can do just about anything you really want to do in life. If you want it, you can “make it happen.”

This belief, or faith, has strengthened over the years as it has been affirmed again and again. First and foremost, you must believe it can happen in order to make it happen.

As leaders in business, we are called to make things happen. We are tasked with building and growing organizations, providing livelihoods and purpose to our employees, and making a difference in our communities. And we must do all this while maintaining our personal integrity.

Making it happen as CEOs and leaders, especially when our companies are facing new obstacles, needing focus and redirection, can feel overwhelming. Sometimes the mission seems impossible.

Yet you can make it happen. Over six decades, I have worked with organizations and teams that aimed to achieve big, “impossible” things and did. In the 1960s, I worked with NASA on the mission to put man on the moon. I was one of the top six executives in the Apollo Program Management Office at age 29, the youngest man in the US government at that level of responsibility. We, with 450,000 NASA and contractor people, made those successful lunar landings happen.

Many years later, I was asked to lead Tracor out of a jungle of problems. Tracor, the first company based in Austin to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange and on the Fortune 500 company list, had been purchased in an ill-fated leveraged buyout in the frenzied period of such deals in the 1980s. Tracor was an electronics engineering, manufacturing, and service company with a large defense business segment. Between a stock and bond market crash, the fall of communism, and the resultant reduction in defense budgets, it was suffering from steep debt and declining revenues.

I began as CEO of Tracor on March 1, 1990, and began forming a new team to lead it through restructuring. Through business sales, closures, and spinoffs, we reduced Tracor from $750 million in annual revenue to primarily a defense company with some $250 million in revenue for 1991. We then grew the company to a Fortune 100 fastest growing company in 1994 and achieved $1.3 billion in the year before Tracor was acquired by GEC Marconi in June of 1998. The sale price was $1.4 billion or more than one times sales, very high for the industry at that time. Once again, we had made it happen.

What were the common characteristics in these situations and several in-between where similar successes were achieved?

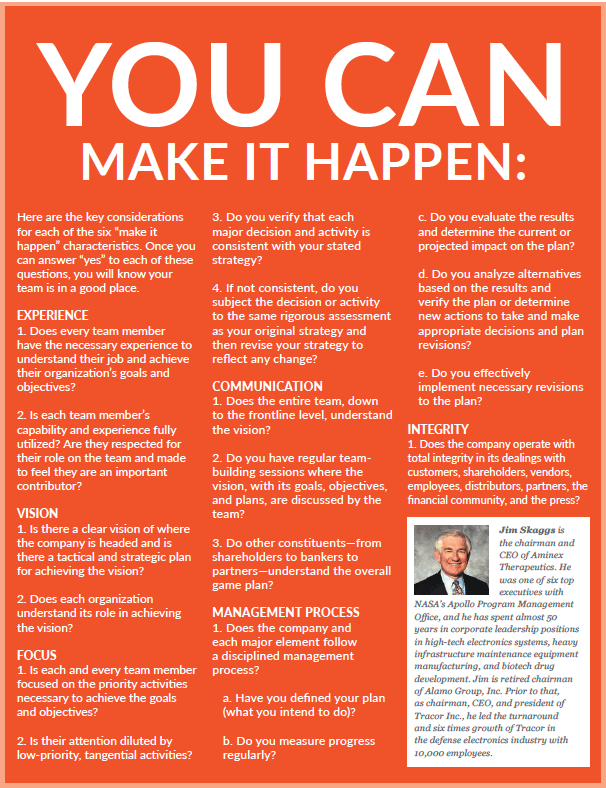

I have developed a list of six common characteristics that teams need if they are going to make it happen. They were developed to apply to the corporate context, though you may also see applications in your personal life. Regardless, if you want to make it happen, ensure that these six pieces are in place.

Six Common Characteristics

1. Experienced/Quality People

People with both experience and quality are indispensable in times of challenge and change. People who have experience without quality or quality without experience do not make the list. You need both traits.

You need the right experience to do a tough, complex job. Money will not substitute for experience. I have seen many instances where inexperienced people threw money at a problem with little result. The difference between experienced people and inexperienced, even bright, people is very great, and it’s often the difference between failure and making it happen. You must have key people with applicable battle scars.

By the way, I place as much or more responsibility on those selecting the unqualified people as I do on the actual people who perform poorly when placed in a job for which they are not qualified. Also, note that experience is not the same as time. One can work 10 years in a job and have less experience than one working one year in a rich growth environment.

Much management writing identifies intuition as a common characteristic of top performers. What, really, is intuition? I believe it can be defined as the sum of all your experience coupled with the ability to access and apply it. In other words: The greater your experience and your ability to reach within to bring forth and apply its lessons, the greater your intuition.

NASA’s top executives recognized the need for experience and implemented a process for assembling a seasoned team that could make a lunar landing happen in a relatively short time. Some years later, the second and third teams at NASA didn’t have the same level of experience. I believe that we suffered the first Shuttle disaster because of it.

Under this heading of experience, I include the effective use of the experience of your people. You achieve maximum value from a person only in their effective participation as a team member. I have been impressed again and again with the ability of teams to arrive at the “right answer” when the right experience is tapped. A true team member must fully respect the roles of all team members.

I temper “experience” with “quality” for a reason I alluded to above: Not all experience is equal. The person who has the experience must be a person of talent, integrity, and drive as well. Once you bring quality together with experience that fits the mission, you have someone who can truly help you make it happen.

2. Vision

I believe that value starts with vision. Before you can make it happen, you must know exactly what that “it” is. You must have a vision that is based on a thorough understanding of the company’s capabilities and the marketplace. The vision must be challenging but realistic and come with a master plan that shows how you will achieve it. The vision and plan should be jointly developed by the team and well understood and communicated to all levels of management and to all employees.

Generally, the vision begins with the company’s strengths and builds from there. The vision and plan are not static or frozen. In a world of an increasing rate of change, you must be flexible and continually adapt as necessary. A major requirement is to make timely, key decisions that respond to major needs. Without decisions, one cannot advance.

Vision is not a pie-in-the-sky dream without regard for the realities of the marketplace and your team’s capabilities. Many times, companies will form visions that are not founded on a thorough understanding of reality. Thus, they cannot build or implement a viable plan. These wishful thinking exercises will almost always fail, and be very costly.

For example, Tracor struggled in the 1980s partially because it had made so many acquisitions. In each of those companies, we found substantial efforts to diversify into markets in which they had no experience. Not only were these diversifications failing in every case—they were also distracting management attention from major core markets and degrading overall performance. In each case, we stopped the diversifications and focused management on core businesses. Immediate, major improvements were experienced in sales, profit, and attitude.

In establishing a vision, don’t fear risks, but understand them, for they are present in all aspects of life. The greatest economies in the world are based on taking risks. People are motivated to take responsibility and make risk judgments and decisions because they are rewarded for success. In many cases, our government institutions are very inefficient because they do not reward success, which encourages risks. Instead, they reward the lack of failure. This affliction is not limited to government organizations but is found in many bureaucratic organizations. But taking manageable risks is an important aspect in any person’s or venture’s growth and success.

I have followed my own golden rule of risk throughout my career: Take prudent, manageable risks but never “bet the company.” In other words, don’t take moderate-to-high risks that could destroy your organization, but prudently take smaller risks that could pay off in the end.

3. Communication

Good communication is vital to almost every aspect of leadership. Early in the Tracor restructuring, it was vital for us to recognize that we had several major constituents, any one of which could send us to liquidation. It was very important for us to maintain credibility with customers, employees, bankers, vendors, bondholders, and shareholders. We gained credibility and support from each of those groups primarily through frequent, honest communication—and by always doing what we said we would.

Communication from the CEO is particularly critical for team members, who must feel part of a team to be of maximum value. Employees must understand their company’s objectives, their unit’s objectives, their own objectives, and such things as retirement plans, medical plans, and other benefits to be of maximum productivity. Abundant communication from leadership equips them with this knowledge, which enables them to perform.

Good communication is also vital to effective teamwork, and teamwork is required to accomplish tough, complex tasks. Individuals do not make it happen—teams do. And remember, team members don’t have to like each other, but they must respect each other’s role on the team. Communication is the best tool for working out this friction as it arises.

Communication is two-way. You must be a good listener. You will get no input from your team if you “know everything” and are always on transmit. Always remember: There is no monopoly on good ideas.

4. Focus

As previously discussed in the vision section: Don’t dilute important management time, attention, and resources to ill-advised diversions unrelated to core business activities.

At Tracor, all of our potential and completed acquisitions were trying to diversify because they thought it was appropriate to counter the declining defense budget. Everyone seemed to be telling the industry to diversify. So these companies were all dabbling in state and local government as well as the medical and telecommunications markets. They were not qualified for these markets, which are totally different from the US government market. We made Tracor happen because we stopped these distractions.

Earlier, in the 1970s, there had been a concerted effort for such companies to diversify into the energy market. This was also a bust for most.

Another “focus” challenge at Tracor was the need to run the company and address its performance issues even as we worked through a comprehensive restructuring. One action we took was to create two chief financial officer roles: one focusing primarily on company operations and one on the restructuring. This worked extremely well. Each CFO could harness focus on their respective area.

At NASA, focus mattered immensely. We knew that if we were going to achieve the lunar landing by 1969, we had to stop studying alternatives endlessly, select an approach, and move forward on it with intense concentration. Some of the scientists would have happily studied the problem for many more years without experienced, capable program management that pushed them to focus on a workable solution in the necessary time frame.

Almost always, the first thing you find missing in a troubled company, program, project, or activity is a lack of fundamental management processes.

5. A Fundamental Management Process

Almost always, the first thing you find missing in a troubled company, program, project, or activity is a lack of fundamental management processes. There is no magical fix to tough, complex problems. The only true solution is the disciplined and structured application of the basic management processes that have been around for a long time.

Whether at the level of a whole corporation, a major program, or a small project, you need a management process that includes the following five elements:

a. Establish a baseline (what you say you will do).

Describe what you are going to do. This is your plan, your goal. It can be expressed in documents, specifications, project budgets, schedules, etc.

b. Measure progress.

Measure progress against your commitments on a regular basis. Depending on the situation, it can be weekly, monthly, quarterly, and/or annually.

c. Analyze and evaluate performance against the plan.

Is the measured progress aligning with the vision? Is it getting you closer to making it happen? If corrective action is needed, examine alternatives.

d. Select alternatives as necessary.

If you determine a course correction is needed, determine the appropriate actions in a timely manner, make decisions, and communicate them widely.

e. Update the baseline plan.

Revise the baseline plan—what you say you are going to do—in a documented manner. Then, assure everyone understands they are accountable to this new baseline.

As you will note, the fifth step creates a closed-loop management process. This is a living process requiring discipline and continuous attention to detail. A similar closed-loop process can serve you in everything from the smallest everyday endeavor to the most complex, massive projects.

And last, but by no means least important, you must:

6. Operate with integrity in every aspect of the business.

In all dealings with all your constituents—customers, shareholders, vendors, employees, distributors, partners, the financial community, and the press—you must:

- Operate in accordance with all laws and regulations.

- Operate with the highest standards of ethics.

- Maintain full, honest, and clear communications.

- Operate with fairness, remembering that fairness is not always found in a procedure or policy. Sometimes rules and regulations are not fair. Search from within to find fairness.

- Do what you say.

- Be dependable and reliable.

- Maintain credibility.

There is not much more to say about integrity. You know it when you see it. And leaders should hold on to it dearly because once it is lost, it is gone.

• • •

These underlying traits of leaders and businesses that make it happen are not particularly complicated. But when a group achieves something significant, especially in a time of transition or against the odds, you can be sure that these items are in place.

A final thought: One underlying theme that emerges from these six principles is the importance of continuously creating a small company atmosphere within a large company. These traits—vision, communication, focus, etc.—are often things lost as a company becomes bigger and bigger.

No matter what size your company is, though, if you adhere to these six principles, you will create highly motivated teams that will make it happen.