Another Texas Company Launches into Space

As of late August, Austin-based R&D lab Nanohmics has officially begun its first test of a product on the International Space Station. Nanohmics president and cofounder Mike Mayo spoke with us about hyperspectral imaging sensors, his hands-off leadership style, and why Texas is the place for space.

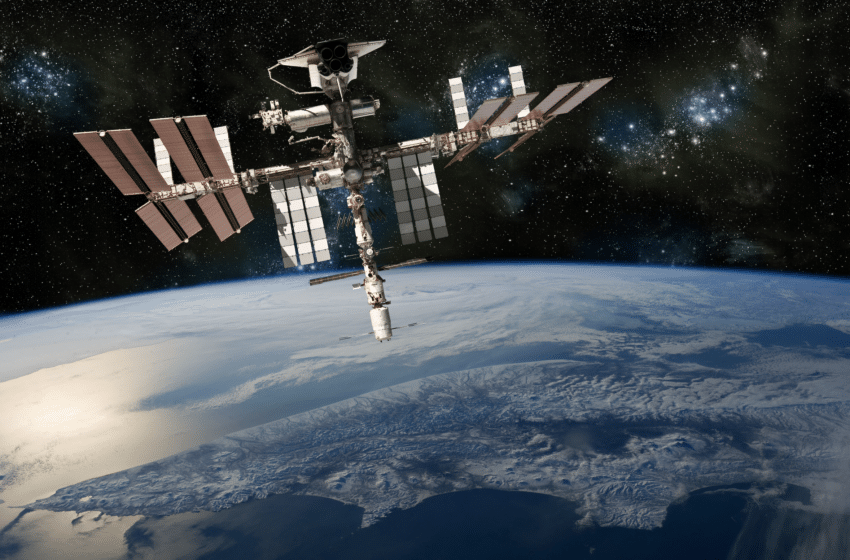

Early in the morning of August 28th, around 3:30 a.m., a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket blasted off from Launch Complex 39A at the Kennedy Space Center on the eastern coast of Florida. The mission is known as CRS-23, because it marks SpaceX’s 23rd Commercial Resupply Services flight to the International Space Station.

On board the Falcon 9 was a tiny but mighty piece of tech: a prototype of the world’s smallest hyperspectral imager. The prototype was developed by Nanohmics, a research and development lab headquartered in Austin, along with the University of Maryland and NASA’s Langley Research Center.

As he made a road trip from Texas to Florida to attend the launch, Nanohmics cofounder and president Mike Mayo carved out a few minutes to answer our questions about the spectral imager, his approach to leadership, and more.

Thanks for talking to us, Mike. Can you first explain what “hyperspectral imaging sensors” do, exactly?

They basically help you look at the color content of different objects. There’s a lot of information you can gain from the spectra that an object is putting out. Right now the main application is atmospheric sciences—gathering climate-change data, looking at forests and coral reefs, gauging crop health. But there’s a whole host of uses. Everything from classifying structures for the self-driving auto market to recognizing the chemical signatures of weapons of mass destruction or different chemical agents.

What is the significance of this launch for hyperspectral imaging technology and for Nanohmics?

This is our first product to be launched into space, so we’re excited. This product line was developed through a series of government grants, for application primarily in the military market. On this flight, we won’t be collecting a lot of scientific data. It’s really more about the flight heritage [proof that the product works in space] so we can advance the technology.

Right now, airborne hyperspectral sensing consists of very large systems. But the technology we’ve developed is only a couple of grams as opposed to pounds or even tens of pounds for the typical setup.

You cofounded Nanohmics in 2002, correct?

That’s right.

Can you tell us a little bit about what the company does and your vision for it?

Nanohmics is a technology development company that tackles challenging problems we want to solve. We have 50 people of various backgrounds, material scientists, chemists, physicists, electrical and mechanical engineers. We’re multidisciplinary, so we don’t really have a target product line or a target market. We try to develop patentable technology that can advance science—and benefit the US economy. You could say we’re a technology incubator.

Are you originally from Texas? If not, what drew you here?

I’m not originally from Texas. I spent 10 years in the Air Force, and my last assignment was in Baltimore. I was drawn to Texas via another small company I worked at prior to Nanohmics.

The advantage of Texas for us in particular is the Austin tech base. For example, a lot of this sensor that we’re launching is fabricated at the shared-use facility in the semiconductor lab at University of Texas, which is funded by the National Science Foundation. That allows small companies like ours to get access to millions of dollars’ worth of equipment at very low costs, on the order of $50 an hour.

Is most of your workforce based here in Austin?

We’re all here in Austin.

Obviously, Texas has a long history with aerospace, and we’ve recently seen Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos basing launches from here. Do you think that type of activity will increase in Texas?

I do, especially with the standing up of the Army Futures Command in Austin. That’s drawing a lot of activity in the aviation space and especially the software and AI space.

What is it like to lead a team of so many highly technical people?

To be totally honest, I don’t have to worry too much about it. Our people are highly self-motivated, so I can’t really pat myself on the back for that. It’s kind of like a self-driving car. We’ve got a very flat organization.

A lot of people think that in the military, if you’re in charge, you tell everybody what to do. But it’s really not that way.

Do you find yourself using any of the principles you learned in Air Force in your role as president?

I think I do. I’ve always taken the approach of allowing people with expertise to do their job while the leader shields them from other duties that would detract from their work. If I’m pushing down management or other responsibilities that water their work down, we’re not accomplishing the mission. I did learn that in the military.

A lot of people think that in the military, if you’re in charge, you tell everybody what to do. But it’s really not that way. If you have a highly trained fighter pilot, you want them to be working on that skill set and applying those skills, not doing a lot of bureaucratic minutiae. I’ve learned to take on those management tasks to allow people to work in their areas of competency. My personal philosophy is that allowing people to do what they’re good at usually has the best outcome.