Sustainability: Who Gets to Decide?

In September of 2020, the Big Four accounting firms announced a new reporting framework for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards. The announcement captured attention because it marked a joint initiative between the four largest accounting firms, which is not an everyday occurrence.

When the World Economic Forum’s International Business Council (IBC) championed this reporting framework—in hopes that the more than 100 global companies populating the IBC would adopt the standards for 2021—the reporting framework gained momentum. However fast (or slow) this new ESG reporting framework is ultimately adopted, it will most likely impact how companies report their sustainability performance and could be a key component of the World Economic Forum’s “Great Reset” initiative.

Reporting standards like ESG and others raise important and fundamental questions about the nature of sustainability. Do reporting standards help achieve improved sustainability and increased innovation, or do they thwart sustainability and stifle innovation by creating uniformity and ease for those reporting and reviewing? How do we know what “good” sustainability performance is? Is it possible for a company or a nation to effectively measure progress toward sustainability? Are the best intentions of companies moving us toward a more sustainable world, or could they be a catalyst moving us further away from such a world? How will we know?

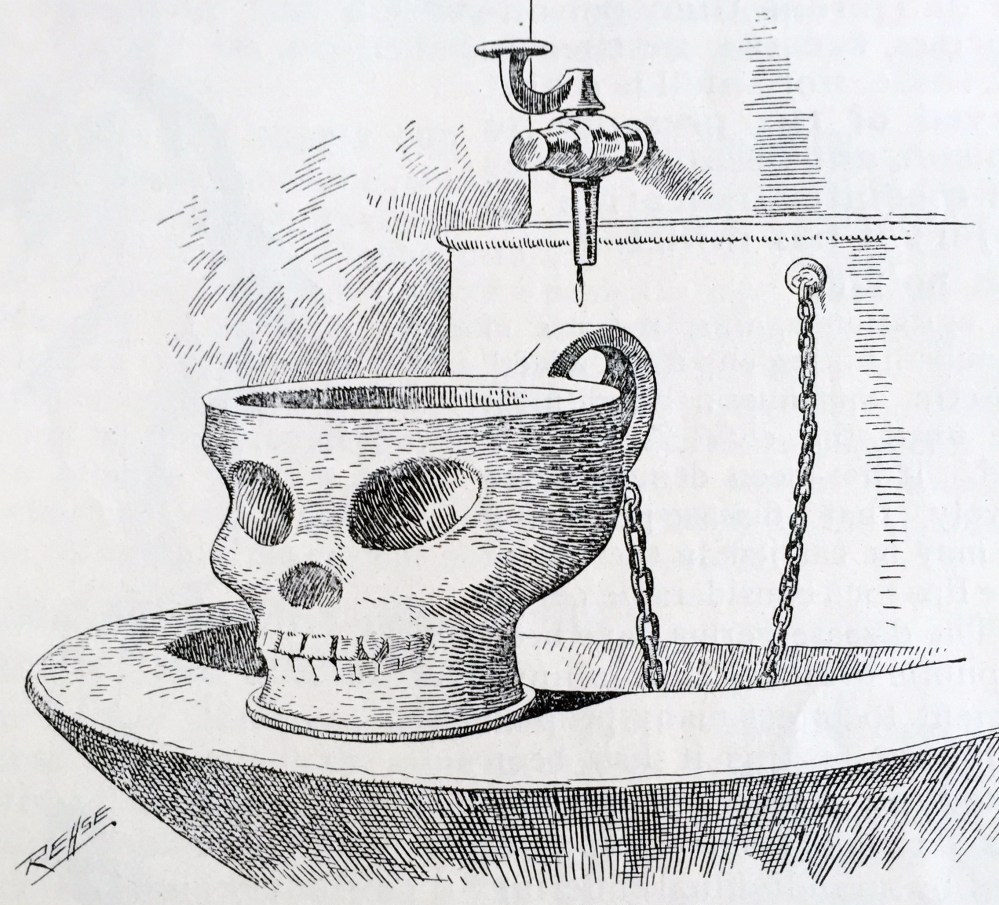

Let us explore those questions in light of a common example, the disposable paper cup. Single-use products are much maligned by sustainability advocates as wasteful and unsustainable. Yet single-use products, including the disposable paper cup, made a comeback in 2020 due to the global pandemic. The disposable cup has always required valuable inputs (trees, energy, water, and chemicals) and created waste, including manufacturing residuals and used cup waste. Those are often viewed as “bad” by sustainability standards. But those inputs and the resulting wastes generated go toward creating something society highly values. Historically, the disposable cup came into being as a social “good”—a way to improve quality of life by slowing the transmission of disease at community drinking buckets found in public schools, public buildings, and railway stations.

The campaign hit critical mass in 1908 with the publication of Professor Alvin Davison’s study of the contamination in school drinking cups, called Death in School Drinking Cups. In many places, disposable cups cost thirsty users one penny per cup of fresh water. On the other hand, communal drinking buckets were free, didn’t generate paper waste, and required only a modest social accommodation—sharing a dipper—to use. Nonetheless, communal drinking buckets actually lowered the quality of life among many users and imposed dire costs by spreading disease and death. Surprisingly, the disposable paper cup emerged as the most sustainable way to provide a refreshing drink of water in public places while minimizing the spread of disease.

Courtesy of The Hugh Moore Dixie Cup Company Collection, Skillman Library, Lafayette College

Disposable paper cups continue to provide hygiene and convenience to more users than ever before. And they are made with a renewable resource—trees—which is turned into pulp at primary manufacturing plants fueled in large part by renewable biomass fuels. In addition, they can be recycled or composted for future reuse where the applicable recycling or commercial composting services exist. These aspects of disposable paper cup production would be deemed good sustainability performance by most measures.

The ongoing value of the disposable cup illustrates many of the challenges associated with sustainability initiatives. For most products and projects, it is nearly impossible to anticipate, properly evaluate, and effectively weigh the value of the various factors leading to sustainability with simplistic measures. Value is always subjective. How can a “standard” for sustainability capture the subjective nature of value? As is the case with the disposable paper cup, some may value hygiene over cost, while others may not. Who should decide? In the case of the disposable cup, the market got to decide and valued the cup’s social, environmental, and economic benefits more than the perceived downsides.

Sustainability is not static. Innovation and other local or global changes can, and often do, change the equation. Ill-conceived sustainability can be like an ill-conceived diet. Dieting can certainly have health benefits, but a poorly designed diet can be unhealthy and even kill you. The dieter should know what they are trying to achieve and when to make modifications or stop altogether. People typically choose to diet because they create a vision for some improved future state of health or appearance. This improved state might be about weight loss or it might be about improving nutrition. Similarly, businesses should have a vision for improved sustainability so they know what is important, why it is important, who values it, how much they value it compared to its trade-offs, and how to effectively measure future performance. Like poorly designed diets, poorly designed sustainability activities can start well but end up injuring business performance.

As a business gets started on developing more formal sustainability reporting under one or more ESG standard, there are some foundational concepts and definitions that executives should clarify up front.

Some good initial questions to answer include:

- What is sustainability, and what determines “good” and “poor” performance?

- Why does sustainability matter to this business?

- Who are the key stakeholders driving our sustainability agenda?

- What specifically are those stakeholders interested in, and what level of performance will satisfy them?

- What is sustainable about our current performance and what threatens our sustainability?

- How do we know how we are performing on those issues relative to our competitors?

- As we strive to make progress on those issues, are we getting more sustainable or less sustainable as a business, and how will we know?

- Who gets to decide what outcomes qualify as more or less “sustainable”?

- How should we report our sustainability performance in an authentic and meaningful way, and does a standard (or standards) help?

In the pursuit of sustainability, common definitions and shared understanding are also important. It is hard to build a sustainability capability and drive performance if words and concepts aren’t clear. Following are some of the more critical terms and questions upon which to seek clarity.

What is ESG?

ESG is simply the acronym for sustainability reporting and measurement, often in the framework of environmental, social, and governance that is currently popular with financial, investment, and accounting firms. ESG is not synonymous with sustainability any more than a stat sheet is synonymous with a football game. Sustainability is the object of ESG reporting. ESG reporting isn’t the goal; sustainable performance is the goal. The Big Four ESG framework is but the latest among a variety of attempts at standardized sustainability/ESG disclosure frameworks. Other older and well-known examples include the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) framework, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) framework, and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), to name a few. The most valuable way to think about sustainability reporting and measurement is for a company to choose the framework(s)—or create its own framework—that most authentically represents its performance on the issues that are material to its key stakeholders. Reporting on what everyone else reports on might be easy, but it may not represent the sustainability story of a business or industry accurately or be related to what its key stakeholders value.

What is sustainability in business?

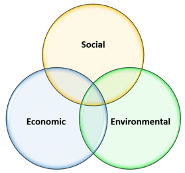

Sustainability is a goal to be achieved. It is a future state that a business is striving to achieve based on current actions that it believes beneficial to its future. The beauty of free-market sustainability is that voluntary exchange and competition allow competing sustainability priorities to be met and avoids the “one size fits all” problem of centrally planned economies and standardization efforts. Sustainability is generally understood in three dimensions commonly referred to as social, environmental, and economic. Focusing on each dimension individually helps to reveal the perceived positive and negative impacts of an activity, which are your opportunities for improvement. Collectively, the goal is to optimize the tradeoffs among the dimensions, seeking to minimize the perceived negatives and maximize the perceived positives in a manner that is preferred (or is at least minimally acceptable) to the key stakeholders of the business. For most companies, the biggest key stakeholders are the customers.

The disposable cup example illustrates how thirsty humans chose preferred social outcomes (avoiding disease and enhancing convenience by use of a disposable cup) despite worse economics (a penny per cup) and some perceived adverse environmental outcomes (resource use and waste). Yet voluntary decisions by those paying the costs and optimizing the tradeoffs created a significant market for disposable cups. And the longevity of this product proves its sustainability.

Is sustainability an absolute?

Sustainability is not a fixed or static thing. It is not an absolute that applies at all times and in all places. Sustainability is relative to the next-best alternative. It can be highly influenced by geography. It is not a place that is reached, but improvement that is continuous and relative to all other circumstances. Consider this question in the context of water waste and water availability. Most people would say that water availability and quality are a global problem. We contend that it’s better understood as a regional, globally dispersed problem. In water-short places such as southern Arizona, inefficient use of this life-sustaining natural resource can lead to business failure and result in human and environmental suffering.

Comparatively, in places where water is plentiful, such as along the Columbia River in northern Washington, water inefficiency (or waste) is more of an economic issue and less a social or environmental one. Water inefficiency may mean that it costs a business in Washington more to pump, treat, heat, and cool water, but that inefficiency may be immaterial relative to other business improvement opportunities. As such, it is potentially unsustainable to address water inefficiency as a high priority in northern Washington. Such inefficiency is depriving no one of water and is not degrading water quality. Further, since water quantity and quality are largely regional issues defined by watersheds, saving water in a water-rich location generally has no benefit to a water-short location in a different watershed. That is, Bill saving water in northern Washington in no way helps Blaine in water-challenged Phoenix.

How do we know today if something is “more sustainable”?

We often hear that one thing is “more sustainable” than something else. How do we know? And who gets to decide? Isn’t value always subjective? It often seems that the goal of many sustainability efforts is to use no inputs, have no waste or emissions, and still make valuable products and services—sort of like turning nothing into gold. At least the alchemists of old used lead in their attempts to make gold. The smartphone, one of the greatest and most popular 21st-century product innovations, certainly did not conform to this “no input, no waste” vision of sustainability.

Early smartphone users likely weren’t concerned about whether their model of phone needed more rare-earth metals, generated more emissions in manufacturing, consumed more energy over its life, or used more packaging than prior model phones. In fact, products that consumers choose every day create some form of waste. Consumers showed that they valued the many benefits and enhanced quality accompanying smartphone technology rather than lament the use of expensive and non-renewable rare earth metals. Think of the time saved and convenience increased due to smartphones. Also consider the material savings resulting from the desktop and laptop computers that were never made or sold as smartphones filled that demand. (On the other side of the equation, we should also consider the addictions, lost productivity, and other adverse consequences of smartphones.) But in 2007, regulators did not try to stifle innovation or influence market choices by defining a reporting standard for a “sustainable phone.” And we should be thankful for that.

Who gets to decide?

Many sustainability efforts rely on government incentives, top-down regulation, and choice-restricting mandates to change consumer behavior for the sake of sustainability—such as California’s recent zero-emissions vehicle mandate for 2035. However, as we’ve noted previously, sustainability is a dynamic, multifaceted, hard-to-predict end state. Georgia-Pacific’s enMotion paper towel dispenser illustrates a product success that defied sustainability predictions with a market-driven, bottom-up story.

If Georgia-Pacific had convened a conference of experts to discuss the most sustainable way to dry hands after washing, the enMotion dispenser would not likely have been the result of those deliberations. Most likely that conference would have skewed toward “environmental” standards such as where and how to source fiber from sustainable forests, which forest certification schemes are required, how to handle the particular chemical compounds used for bleaching, and how much embedded energy from manufacturing is acceptable. It may also have tried to create new economic paths to “profits” by offering tax incentives, or suggesting a solar-powered hand dryer (despite an eye-opening 2014 study in the Journal of Hospital Infection about how jet-air dryers spread far more bacteria than paper towels).

The enMotion dispenser ultimately didn’t have anything to do with the sustainability standards that likely would have been identified for the most sustainable way to dry hands after washing. Georgia-Pacific simply started with a fundamental “social” question: What is the unmet need in the marketplace? You need to dry your washed hands and you don’t want to touch something dirty to do it. The sustainability challenge was whether GP could make the buyer of the towels (most often not the user of the towel), the user of the towel, and the manufacturer of this product all better off so that voluntary exchange would reward its solution. The result was to look at the desired outcomes and perceived downsides in each dimension (social, environmental, economic), then seek the optimal solution among the tradeoffs.

The optimal solution became a portion-controlled dispenser, which became the most popular and hygienic towel system in the market as judged by market share. What were the innovative and sustainable solutions it delivered?

- Social: The dispenser solved the primary dilemma with touchless delivery of a highly hygienic towel that remains in the dispenser, unexposed to bathroom germs until ready for use.

- Environmental: the towel is made from renewable wood fiber and sourced from among the most sustainable forest basins in the world. And the portion-control mechanism of the dispenser results in approximately 30 percent less towel use than the previous largest-share hand towel dispenser, meaning fewer towels manufactured, shipped, sold, used, and disposed of.

- Economic: Customers buy 30 percent fewer towels and save money, and Georgia-Pacific manufactures 30 percent less to dry the same number of hands, while enMotion maintains among the highest profit margin of any paper hand towel dispenser.

We acknowledge the ease of explaining the success of the disposable cups and enMotion dispensers in hindsight. Sustainability, however, is a future outcome and cannot be predicted with such certainty in the present. Since sustainability requires the optimal blend of social, environmental, and economic tradeoffs, freedom of choice in a free market allows voluntary exchange to discover the value of those tradeoffs rather than putting it in the hands of regulators and so-called “experts.” What we ask for as consumers is transparency in the sustainability story of the products we choose.

• • •

The next time sustainability is on the executive agenda, we recommend the following questions to focus the discussion:

- Does your business know who its key sustainability stakeholders are and what issues they care about?

- Does your business know what level of performance is required on each material sustainability issue to satisfy the stakeholder? And how is your level of performance material to your key stakeholders? The social pressure is to be “world class” in all categories, but the actual outcomes can range from “check the box” to “above bottom quartile” to “top quartile” to “best in industry” to “world class.”

- How is your company’s sustainability story authentic to your brand and culture?

- And finally, how do you know whether your company’s sustainability actions are actually sustainable? Anything that is not economically sustainable is not sustainable. Ask yourself, how can anything that is publicly subsidized or mandated be sustainable?

So, will recent sustainability efforts and the continuing push for reporting standards in the marketplace help products and services to be more sustainable? Only time, executive decision making, and consumers will tell. But our best hope is not just in dieting our way to health or having other people prescribe what will make us happy. Our best hope is in our ability to make voluntary choices among competing products and services to find those we believe will improve our quality of life and create greater prosperity for our communities; once we see the results of these choices, we can choose to stay the course or to make changes. As simple products like disposable cups and paper towels remind us, we need to recognize that there is often more to the sustainability story than our preconceptions allow us to see.

4 Comments

Good presentation.we should implement

Future generation will be benifitted

God bless all

Thank you for reading it and your supportive comments.

Bill and Blaine, this is a well-written, thought provoking article. The right questions are being asked, as well as careful consideration of the needs/wants of all parties involved. Now we just need innovative, thoughtful minds to create better practices, materials, processes, and inventions to drive society towards a more sustainable future socially, environmentally, and economically.

Thank you, Michael. Thoughtful and on-target as always!