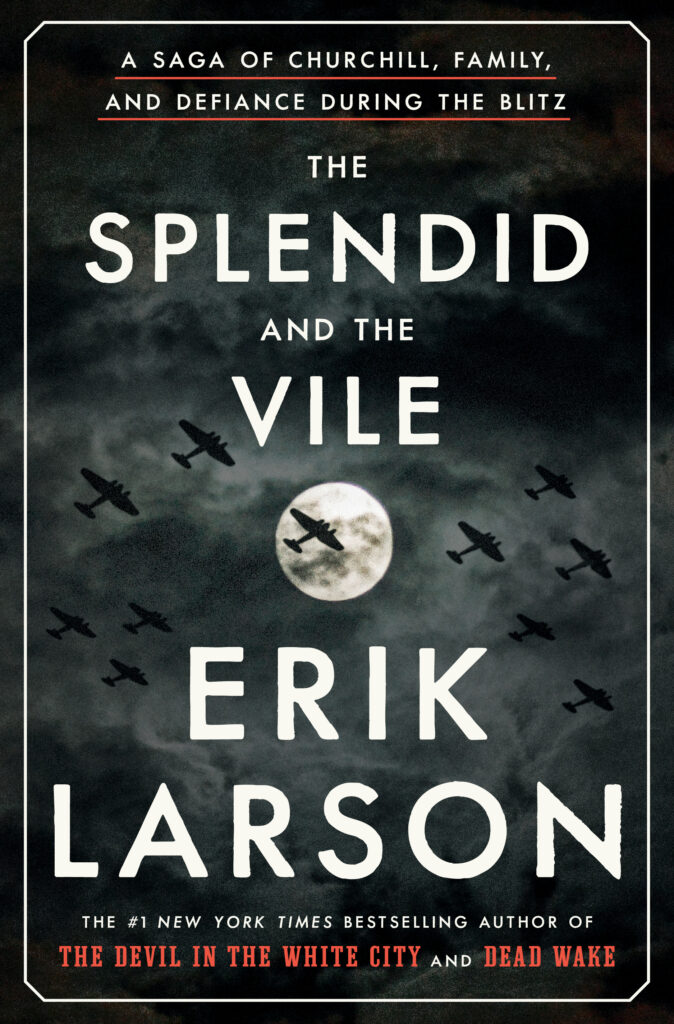

Pulling Together Under Pressure: An Interview with Erik Larson

We’re all familiar with Winston Churchill the wartime bulldog, cigar in mouth and bon mot on tongue. But few have rendered the man and his leadership with the intimacy and gripping drama of Erik Larson’s latest book, The Splendid and the Vile. In it, the six-time New York Times bestselling author pulls back the curtain on Churchill’s first year as prime minister, a year that coincided with the devastating German Air Campaign of 1940–1941. Rather than focus on the broad sweep of history, Larson’s book homes in on the day-to-day experience of a rapidly escalating war, as lived by Churchill, his close circle of family and advisors, and the average citizen of Great Britain.That was a time very different from our own. But, as Larson discusses in this interview, there are parallels to the crises of today, not least of which is the necessity of people pulling together under a period of immense pressure. Though the particulars don’t match—we’re now called to stay home for our country, for example—this pivotal year of Churchill’s career holds plenty of lessons for the leader of 2020.

Many Americans don’t know much about the British governmental system. Can you tell us how Churchill first obtained the prime minister position? Churchill became prime minister on May 10, 1940. He was one of a couple of candidates who were proposed to King George VI. At that point, it was the king who decided who became prime minister, but the king tended to go along with what Parliament wanted. At the time, there had been a political rebellion in the House of Commons against Neville Chamberlain, who was prime minister prior to Churchill. Chamberlain was a very staid guy and had been deemed not quite up to the task of waging war with Hitler. His nicknames were “the Coroner” and “the Old Umbrella.” Churchill, on the other hand, was very popular with the public at that point. There were those in Parliament who felt Churchill would be a difficult character as prime minister—he was full of energy that was directed, as one minister said, “in all different directions at once.” But he was

deeply popular with the public, and the rebels in Parliament thought he had the chops to take on a World War. Ultimately, the king agreed. The king did have grave misgivings about Churchill initially, but not so grave as to attempt to override parliamentary leaders.

Churchill was clearly thought to be the best guy on hand.

And Churchill certainly believed that Churchill was the best guy on hand. That’s absolutely true. Churchill was a hero in the eyes of the public but also a hero in his own eyes.

The important thing to know about Churchill becoming prime minister is that despite the circumstances of the day—he assumed the office on the day that Hitler invaded the Low Countries—he felt that this was the highest achievement of his life. He had worked his entire career for this, and he was delighted. Yes, this World War had just become very, very hot, but now he was the boss. He made himself defense minister, in fact.

Churchill understood strategically that the Americans were key to long-term success in the war effort. How did he develop that understanding? Churchill had done a lecture tour in the United States, and in fact had been hit by a car and seriously injured in New York City. But he did recognize from the very start of his career as prime minister that Britain could not win this thing on its own. Britain could fight to a draw, perhaps, but he knew it could not win without the help of the United States. So, he always acted with one eye on what America would think, with the idea of eventually reeling in Roosevelt. He was like a global fly fisherman, very adept at getting that fly in front of Roosevelt. It didn’t ultimately work until the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

I don’t think most Americans today understand how strong the antiwar sentiment was in the United States at that time. The prevailing opinion was that we should avoid the war at all cost, right? America was profoundly anti-involvement. We did not want to get involved with World War II—though of course nobody called it “World War II” at that point. Roosevelt understood the depth of this antipathy toward involvement, and that made his position very, very tricky. I don’t think Churchill fully appreciated that. A lot of British people couldn’t understand why Roosevelt couldn’t just pull the plug and get into the war. As Churchill came to realize more and more how tricky Roosevelt’s situation was, his own tactics became more subtle. It was a very interesting courtship.

Once Churchill takes over, he’s almost immediately dealing with the fall of France and a potential invasion of the British Isles. For many at the time, such an invasion would have been previously unthinkable. Many contemporary readers don’t recognize how major an event it was that France fell. It completely changed Britain’s strategic assumptions. After the fall, German bombers could reach London and other cities in a matter of minutes. As most citizens in London and along the coast knew, invasion was a very real prospect. Many were certain it would happen within days of France falling.

It was then that the German Air Campaign of 1940–1941 began—I generally prefer that term to “the Blitz,” since the campaign unfolded in phases. The initial approach was to conduct raids by day, but that proved to be disastrous for the Germans. German bombers could only fly to Britain with a significant escort of their own fighters. The escorts had a 90-minute range, and the bombers could not fly beyond that. Without the protection of their escorts, they were toast; the RAF [Britain’s Royal Air Force] was very effective at shooting down bombers. There was, I think, a sense of hubris on Hermann Göring’s part; he thought his air force was hot stuff and a lot better at dealing with the British than it actually was.

The British had tremendous intelligence as to Luftwaffe activities, maneuvers, and orders because of Bletchley Park and Ultra intelligence. The more significant problem was being able to act with any immediacy on what they learned. The British coastal radar systems were very good, so they knew exactly when bombers were leaving the coast of France. But even then, the fighters had to be directed to meet the approaching aircraft, and this required visual contact during the daytime.

Once the Germans realized they couldn’t keep up daytime bombing raids without losing all their aircraft, they went strictly to nighttime bombing. That’s when everything changed once again. Without the need for escorts, German bombers had a much longer range—and

the RAF couldn’t find them in the dark. British radar would spot these incoming flotillas of aircraft, but by the time the word got to command centers, the planes were in a very different location.

Churchill certainly understood the importance of maintaining dominance in the air, right? Churchill wasn’t a particularly good tactician—someone else probably should have been defense minister—but he did understand from the very beginning that all strategic assumptions had changed after France fell. He knew that the only way to prevent invasion was to prevent the Luftwaffe from gaining air superiority over the Channel. And the only way to prevent that was to train as many pilots as possible and make and deploy as many fighters as possible. Ramping up that capability was possibly the most brilliant thing he did.

In that first year, he hired his friend Max Aitken—Lord Beaverbrook—and put him in charge of a brand new ministry, the Ministry of Aircraft Production. Now, Beaverbrook was a newspaper baron and widely reviled in Whitehall, the seat of British government. But Churchill also understood that this guy could galvanize a business. Beaverbrook had taken the Daily Express, a dying paper, and overseen an incredible sevenfold expansion of its circulation against significant odds.

Beaverbrook had never made an airplane in his life, but Churchill saw him as a force that would shake up the aircraft industry and increase fighter production. That turned out to be absolutely true. It was quite a significant move in that first year. Churchill was particularly good at choosing close advisors who would tell him what the ground truth was and not just give him a lot of happy talk. His advisors would also shake things up in the ministries around them.

One of the striking things in the book is your illustration of how life continued somewhat normally—or under a new normal—as the Blitz was occurring. Why didn’t more people leave London once the German air campaign began? There was an initial flight from London, and many people who could leave did. But there were significant industries and government operations in London. A lot of those industries and government operations were vital to the war effort. And people had to make a living—there was no chance of working remotely by the Internet like many have been doing through the current pandemic.

One interesting dynamic of the COVID-19 pandemic is the public’s extensive access to information; in many cases, we know as much about what’s happening as world leaders do. During the Blitz, however, the government was the primary source of information.

To what degree did Churchill filter the information that British people got during his first year of leadership? Churchill certainly had access to the most fine-grained intelligence. It came to him in his secret box, and he generally did not reveal that to anybody; to do so would risk tipping off the Germans that he had that intelligence.

The public did have access to information from a very vibrant, scrappy press, however, and the press was not totally controlled by Churchill. He could require that the press not talk about particular subjects, such as the sinking of the Lancastria, in which at least 4,000 people died.

Churchill barred reporting on that, though it came out eventually. But overall, the press was very lively and active at that time, so the public was aware of most of what was going on.

Churchill also had access to tremendous amounts of information from Home Intelligence, which collected information on public morale. They gathered all kinds of information, including things like conversations at bookstores. Hundreds of different sources went into the weekly Home Intelligence reports about public mood. Through that, Churchill could gauge how he public was feeling about things and how they were reacting to his speeches and so forth.

One thing Churchill knew was that if he was to tell people things that contradicted their own experience on the street, it would be very destructive to trust and morale. Whether he intuited this or learned it over time, he knew to tell the public what the public already knew.

How did his popularity with the public ebb and flow throughout

his first year? In this first year, his popularity with the public was very high, though his popularity with Parliament did ebb and flow. Almost a year to the day of his appointment, there was a brief rebellious flare-up in Parliament, as had happened with Chamberlain before. Churchill deftly turned those debates into a vote of confidence, which prevented parliamentary leaders from criticizing him without real consequences. Ultimately, the rebels conceded that they were not challenging his leadership overall but just wanted to make certain points against him. It was a brilliant ploy on Churchill’s part.

His speeches also had a good deal to do with his consistent popularity with the public. We all know about Churchill’s terrific phrases. “Never has so much been owed by so

many to so few.” Those are great rhetorical rapiers. But to me the real brilliance in how he spoke was in how he structured his speeches.

He would give people a sober assessment of what was going on. He would not pull punches. But then he would come back with real grounds for optimism. Not happy talk, not made-up stuff, but real grounds for optimism. And then would come some great flourish, which sometimes literally got people leaping out of their chairs and running into the streets to help fight the Nazi scourge. For Churchill, it was very important to acknowledge that the public could take bad news, and that’s how he proceeded.

THE MAIN PARALLEL BETWEEN THE TWO SITUATIONS IS THAT WE ALL HAVE TO PULL TOGETHER.

The Splendid and the Vile focuses on day-to-day life. One surprising aspect is that many notable figures, including Churchill’s family, are roaming about the streets of London during the air campaign, going to the theater and nightclubs and so on. In today’s environment, it seems almost unthinkable that these public figures wouldn’t be highly protected at all times. One of my favorite little facts in the book is that one day Anthony Eden was walking through Hyde Park and he decided to take a nap on a park bench. He slept there for an hour. This is one of the most senior men in the British Empire, one of the most recognizable men in the world, and he just decides to take a nap on a park bench in Hyde Park.

Mary Churchill is another terrific historical character and I was very blessed to have access to

her diary. At the time I was given permission, I was one of only a couple of people who had been allowed to actually see it, for which I’ll be forever grateful. Honestly, I think she makes the book.

The beauty of Mary Churchill is that she gives us an unfolding view on how morale and perceptions of the war evolved over that year. The book starts on May 10, 1940, when she is 17 years old. She’s a very smart, astute observer of her father and the world around her. She is thrilled when he becomes prime minister because she understands that this is the thing her father has always wanted. But the family decides to keep her in the countryside at the prime ministerial country home, Chequers, for her own safety.

She wanted to be part of the action, to do what she could to take on the Germans. One of her great regrets was that because she was a woman, she could not fly a fighter plane

or bomber. But at the same time, Mary Churchill was a 17-year-old girl who wanted to have fun, and she did. She went to RAF dances. There are references in her diary to snogging in the hayloft and other stuff—life did go on. Yes, London was being bombed to hell, but out in the countryside, fun was fun. If the RAF held a dance, by God, she was going to go.

Later, she starts working for the Women’s Voluntary Service and next thing you know, she’s running an anti-aircraft battery in Hyde Park. That’s a terrific metaphor for how people coped with the Blitz. Instead of becoming cowering, terrified people, they became actually emboldened as it went along.

The year 2020 is one of those that historians will want to write about a century from now. But I feel sorry for future historians, since most of us don’t keep diaries like Mary Churchill’s. I consider that question from time to time, and feel lucky to have had access to these incredibly rich, detailed diaries. I couldn’t have written this book without them. But I do think that people are keeping diaries about this grave moment; it’s more that historians are going to have different sources. For better or worse, we’re going to have the entire Twitter account of these events. The National Archives is keeping a huge trove of tweets. From a writer’s perspective, Twitter is going to be incredibly valuable down the road because of the immediacy it provides. You’ve got people witnessing things and writing about them in real time. It’s more abrupt and less literary than a diary, but it’s still a tremendous flow of information. Future historians will also have the added benefit of video, from cell phones and Zoom interviews and all that. But having lived this, it’s not going to be me writing about it.

You’ve been in New York, the initial epicenter of the pandemic in this country. Have you seen any similarities between that city during lockdown and London during the Blitz? Ironically, the right thing to do in this case is exactly the opposite of what Churchill tried to inspire the public in London to do during the air campaign. Right now, we want to rouse people to stay at home. That’s the best thing you can do for your country during a pandemic, and it’s very different from what people felt about London during the Blitz. Especially after it became clear that the Germans had given up daytime raids, life really went back to normal during the day. People got out and went to lunch and attended concerts at Trafalgar Square and

so forth, then returned to a state of real fear and anxiety at night.

The main parallel between the two situations is that we all have to pull together. Everybody’s got to do their part, and in this case that means wearing a mask and staying in to the extent you can. One weird thing is that, for whatever reason, people have flocked to this book

for solace over the past several months. To me, this is something of a mystery, because if you’re turning to a time of mass death and chaos for solace, it says something pretty telling about today. But I also get it, because this pandemic is a time when we do all have to pull together.

Looking at how the British people pulled together and survived that intense year was why I did this book in the first place. It wasn’t that I was interested in Churchill; I was interested in how people dealt with the German Air Campaign on a daily basis. As I mentioned in my Author’s Note to the book, that interest came from an epiphany I had when I moved to New York; I saw what 9/11 meant for New Yorkers versus the rest of the world. There was this sense of having your home city violated by an attack, and seeing everything up close and vivid.

My original plan was to find a typical London family in the historical record and write about their experience of the Blitz. Eventually, I thought, “Wait a minute, why

not write about the quintessential London family—Churchill’s?” For some reason, nobody had looked at this intimate side of Churchill, his family and his advisors, during this period. So I knew I would be able to say something new. Despite that fact, I did run into this very intimidating wall of Churchill scholarship. There’s more stuff written about Churchill than probably anybody else on the planet except possibly Hitler.

Do you know what your next subject is? At the moment, I don’t know what I’m doing next. I’m looking. Between books is always the worst time in my career. I just want to get started on the next project.