What’s Your Motive for Being CEO?

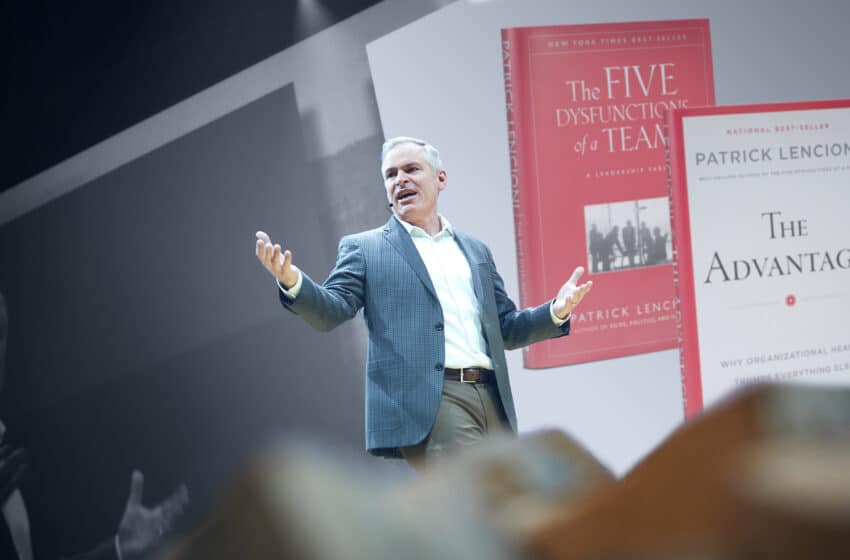

If you’re an executive, you’ve probably got a Patrick Lencioni book on your shelf (or in your e-reader). Lencioni’s works, which include The Five Dysfunctions of a Team and Death by Meeting, have sold over six million copies worldwide — and it’s easy to see why. Each is a marvel of simplicity, embedding sharp, practical ideas about leadership and management into fictional narratives that even the most harried CEO can finish in a day or two.

After early-career stints at Bain and Oracle, Lencioni founded his consulting firm, The Table Group, in 1997. His first book, The Five Temptations of a CEO, came out the following year. Despite the success he’s seen since then, Lencioni and his work are worlds away from the faddish bluster of the stereotypical leadership guru. Lencioni has, in fact, referred to himself as a “reluctant guru.” Reading his work and listening to him talk, the impression is of someone devoted to improving the people side of business — no gimmicks or secret formulas. The approach resonates: The Table Group is a thriving practice, bringing organizational-health practices to clients like Chick-fil-A, Southwest Airlines, Nordstrom, and many more.

And, of course, Lencioni’s books are still selling. That includes his latest, The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important Responsibilities. Through the story of two rival CEOs, Lencioni digs deeper into the psyche of the leader than ever before, asking readers to consider why they are leading at all: Are you a CEO because of the rewards the position brings? Or is there something deeper driving you?

Lencioni recently sat down with Texas CEO Magazine owner Joel Trammell to talk about the message behind his latest book, why he’s changing his mind on virtual work, and which Texas CEOs he’s seen doing a notably good job through the chaos of 2020.

Trammell: At the end of The Motive, you write that it’s the shortest and simplest book you’ve written, but maybe the most important. Let’s start there. Why is this book so important?

Lencioni: It’s one thing to think about how to be a leader. It’s another thing to ask yourself why you chose to become a leader. If you get that question wrong, none of the other stuff makes sense. Our initial motive for becoming a leader is what informs whether we’re willing to do the hardest parts of our jobs.

Trammell:When you work with a new leader, how do you pull their motive out of them? That’s a pretty deep question, right?

Lencioni: The problem is that a person’s leadership motive is not black and white, and it is not always the same over time. People who are currently leading for the wrong reason can change and do it the right way. And people who are leading for the right reason can slide back into a lesser motive if they take their eyes off the ball.

When talking with a CEO, I want to understand whether they are primarily motivated by reward. Reward-centric leadership is not what you want in a CEO; it’s the idea that they worked hard all through their career and now get to have a pleasant and enjoyable time as a leader, without any of the discomfort that comes with the job.

Rather than just ask the question “What is your motive?,” I point out the things that most leaders abdicate if they are reward-centered. I ask the leader, “Do you tend to avoid, delegate, or abdicate any of these five things, which are largely uncomfortable?” Even really well-intentioned leaders will look at the list and say, “Crap. I don’t do those things. I think my motive isn’t where it needs to be.”

Trammell: Let’s dig into some of those things that people tend to avoid. The obvious one that comes up with almost every leader is having difficult conversations, and you write about that in the book. No one wants to have a difficult conversation, but that may be the most important conversation to have.

Lencioni: Nobody went into business so they could have uncomfortable, awkward conversations with people. And all of us can relate to wanting to avoid those. The problem is that if the leader of an organization is not having those conversations, then nobody else will. The purpose of our job is not to entertain ourselves or enjoy ourselves. First and foremost, it’s to do what our organization needs in order to be successful. That doesn’t mean the job isn’t at times enjoyable, but we, as leaders, have to be the first to step up to do the uglier parts of our job. Nobody else can do them if we don’t.

Trammell: I often hear a leader say something like “Well, I can’t just go tell that person they did a terrible job,” or “I would tell them that, but . . .” Every time I hear that, I cringe and know that’s a conversation that was missed. And once you miss the first conversation you should have had, then the second one builds on it. After the third or fourth, then there’s this scab you can’t just tear off anymore, because there will be serious bleeding at that point.

Lencioni: That’s right. We have to realize two things. First of all, when we say, “I don’t want to do that” or “I’m too busy” or whatever else, it’s an excuse. Second, we have to realize that avoiding or abdicating that thing is sometimes an act of selfishness that we’re disguising as an act of caring. In other words, when we say, “I don’t want that person to feel bad, so I’m not going to go talk to them about that,” what we’re really saying is, “I don’t want them to blame me for feeling bad. I don’t want to have to deal with them.” But avoiding that conversation is in the leader’s best interest, not in the other person’s. I’m as guilty of this as anybody. I’ve learned it the hard way over time.

If you avoid a conversation about an issue, that issue is going to come back to haunt that person later — a project or a performance review or, heck, even a personal relationship will go wrong. If we’d only said to them, “Hey, it doesn’t work when you act this way or when you do this,” we could have done them a great service in their career and in their life. When we don’t, we’re essentially saying, “I don’t really care about you that much.” Difficult conversations are, at the end of the day, an act of love.

Trammell: That’s a great point. Another thing you say that reward-centric leaders avoid is developing the leadership team, doing that team-building work. Why do CEOs see that as so difficult?

Lencioni: Sometimes leaders will say, “I don’t have time to do this touchy-feely stuff of ‘team building’ or ‘developing teamwork.’ I’m going to hire a consultant to do it.” Or they’ll say “I’m going to let HR take that,” or “We’re going to all go golfing and that’ll be our team building.” Building your team is one of the most critical parts of a CEO’s role, and it makes everything else easier if we do it well.

But there’s often emotion involved in that part of the job. It’s not easily predictable. And it can be uncomfortable, because you have to get other people to work with one another and confront one another when needed. So a lot of CEOs just bow out of that responsibility. They say, “Well, I brought in that consulting firm to do a half-day session with hugging and trust falls, so I think we’re fine.” That’s not what this is.

Trammell: I know your team at Table Group does a lot of team-building work within executive teams. What are realistic expectations for that kind of work? How fast do you see results?

Lencioni: If a CEO commits to this, they will see tangible, meaningful goodness in days and weeks. Not months and years. Literally. So, while it obviously takes ongoing work, putting the concerted effort into building the team over a couple of days can really change things. You can see real benefits quickly. When we work with executive teams, we make sure that the work we do has a practical outcome. If the team is aligned, work will be more enjoyable and they are going to get more done in less time with fewer mistakes.

Then working as a team just becomes a matter of discipline. If you’re prepared to stick with it, the benefits stay. So many leaders sign up for these things, but they don’t plan on actually following up and doing anything. They can go through a program for a year and not see a difference.

Trammell: Let’s talk about meetings. You wrote a whole book on them, of course. I don’t think anybody wants bad meetings, but what do CEOs do to sabotage themselves in that area?

Lencioni:The first thing they do is convince themselves that it’s okay to admit that they don’t like meetings. They decide it’s fine to treat meetings as just something to get through — when, in reality, meetings are the central activity of a CEO.

If I were evaluating whether Dak Prescott was a good quarterback, I’d watch his game. If I were evaluating whether my son’s teacher was a good teacher, I’d watch him in the classroom. If I were evaluating whether a CEO is a good CEO, I’d watch her during meetings. If those meetings are not focused, if they’re not intense, if they don’t lead to good decisions, and if people are not engaged, I would say that person’s not doing their job well.

And yet so many CEOs will say, “Yeah, I hate meetings. They drive me crazy. But we have them anyway. We just try to make them end on time and get out of there so we can do real work.” Well, that’s not a great approach, because the real work of a CEO is to run fantastic meetings.

Trammell: You talk about constantly repeating key messages to employees. I think some CEOs are scared they’re going to be the old guy who walks around and tells the same five stories. Right?

Lencioni: Exactly. They feel like they’re going to insult their audience, or they’re going to bore them, or that it’s redundant and they’re wasting their time. That’s not how it works. Gary Kelly at Southwest Airlines, who’s a friend of mine and just a dear man and a great leader — that guy knows that his primary job is to be the CRO in the organization, the Chief Reminding Officer. He is constantly finding new ways to remind people of the fundamentals: why they’re in business, what they do, and how to do it well.

The best companies have leaders who are constantly repeating themselves and reinforcing things, just like the best parents do. I like to say that if you’re a CEO and people can’t do a good impression of you when you’re not around, you’re probably not communicating enough. And yet, most of us don’t really want that. We want to just move on to the next topic.

Trammell: Let’s talk about one more thing you say that reward-centric leaders avoid, which is managing subordinates as individuals. In my experience, CEOs tend to think, “Heck, these are all execs. They’re senior people. I shouldn’t have to manage them.”

Lencioni: Exactly. The CEO became the CEO because he or she was a really good leader and a good manager. When they first got promoted to management, they were one of the best managers. They managed and managed and managed. Then they get promoted to CEO and they go, “Finally, I don’t have to do it anymore!” But no, everyone needs to be managed. The executive vice president of the most sophisticated worldwide multibillion-dollar organization needs to be managed — maybe differently than a line employee, but they still need to be managed.

Too many CEOs say, “Well, I’m just going to hire experienced executives who are adults, and they won’t need me to manage them.” Then they’ll excuse themselves and say, “Well, I’m not a micromanager, and I trust my people.” What I always say is, “Hey, managing people is just sitting down with each of the people on your team to make sure they know what they need to do, helping them understand if they’re succeeding or not, and then providing whatever coaching they need if they’re not on target. That’s what management is. If we don’t like doing that, whether we find it tedious or we’re tired of doing it, then we’re probably not being a CEO for the right reason.”

When people become CEO for the wrong reason, it’s usually not just to gain money or power or fame. A lot of them do it because they think it’s going to be fun and enjoyable. That leads them to punt on the parts of the job that are not that enjoyable but that need to be done. The truth of the matter is, the CEO’s job isn’t supposed to be the most fun job in the company. It’s supposed to be the most important one, which means you have to be willing to do the dirty work when it needs to be done.

Trammell: I often see CEOs who confuse management with training. So they’re reluctant to manage an executive because they think it’s the same as teaching the executive a skill. The example I’ve used is that Bill Belichick coached Tom Brady even though Belichick never played a down in the NFL and certainly never played quarterback. But people sometimes think, “How could I manage my chief legal officer? I’ve never been a lawyer!”

Lencioni: Yes, that’s another problem. So many people grew up thinking, “Let’s find the most competent individual contributor or specialist and turn them into a manager.” That’s not recognizing that management is its own genius.

When it comes to the Xs and Os, Bill Belichick is a genius. He knew that his job was to coach Brady. The funny thing is, he never stopped coaching Brady. Even when Brady was famous, he would treat him like a player. He had no problem lighting up Tom Brady if he did something wrong, because he knew that was his job. I think most people would go, “You don’t need to coach Tom Brady anymore.” Well, actually you do, because he’s a player, and players need coaches. If we stop coaching people because we think they’ve hit a level where they don’t need it, well, they’re probably going to need it soon.

Trammell: Your name is synonymous with organizational health. How do you think the last six months of human health issues have impacted organizational health?

Lencioni: I talk about this a lot lately. During times like this, no organization is going to be left unscathed. They’re either going to get better or they’re going to get worse. Some organizations said, “During this time, we are going to focus on getting rid of any politics or confusion or lack of clarity in our organization. That’s how we’re going to spend our time, so that when things come back, we’ll come back stronger.”

Other organizations have sat around complaining or waiting for things to get resolved. By the time things turn around — and I think things are starting to —they’re going to be all the worst for it. The question is whether the organization is going to intentionally get better and separate itself from the pack, or whether it’s going to drift with the current and find itself way behind.

Trammell: What do you think about the role of virtual work in this crisis? I’ve had employees who could have gone and worked from Alaska for two years without a significant impact in their job, but that was because we already had a relationship. Seems to me, assimilating new team members in the virtual world is a lot more difficult than it is in the physical world. Do you agree with that?

Lencioni:I do agree with that, but I don’t think that virtual work is as detrimental as I used to. Heading into this shutdown, I was a pretty loud critic of people who tried to justify virtual work just for the sake of virtual work. I would have told you it’s only 30 percent effective. Today, I think it’s about 80 percent effective. I’ve seen teams who, by being intentional about it, have actually gotten closer and improved their behaviors after going virtual.

Even as a former critic of virtual work, I can see that there are actually a few advantages. One is that you’re dealing with one another from your home environment, and that tends to reinforce people’s humanity and allow them to deal with one another in a more human way. When you see somebody’s child or dog or husband or wife, or when you see them sitting in their living room from time to time, you’re reminded that this is a human being. When we see that, we tend to be a little bit more vulnerable and more gracious with one another.

All other things being equal, I would much rather have people in person. But teams that use technology well are actually finding ways to grow, and they’re going to come out of this stronger.

Trammell: This issue of Texas CEO Magazine honors exceptional leadership on the part of Texas CEOs. You get to see a lot of great companies and great leaders. Any you’d like to point out that you think have done a great job during this difficult stretch we’ve been in?

Lencioni: There are many. Brian Tyler, the CEO at McKesson, is fantastic. When the pandemic started, they were right in the middle of all of it, being in healthcare. Brian doubled-down on building stronger personal relationships with his team over Zoom and other technology, because he knew that was going to be critical to keeping them positive and invested. I think they’re doing a really good job in a very difficult time.

Gary Kelly at Southwest is another one. This is not the first time Southwest has been through a rough period — there was 9/11, of course. But Southwest just finds a way to keep their people rallied, to keep them feeling like they’re a part of the company. They talk to employees and tell them the truth.

Brian and Gary are both being remarkably human through these challenges. They’re engaging with their people and confronting things in a very real way. There’s something about that that instills trust and confidence in people. There are many more CEOs out there doing the same, and most of them are not well-known.

Trammell: Final question. What’s next for Lencioni?

Lencioni: I’m more engaged right now than I’ve ever been. The shutdown led my business to innovate and question some things. We’re about to come out with a few new things that we think will have a profound impact on consultants and managers and employees. And because of the shutdown, we stopped doing some things that we used to do. Our podcast, At the Table with Patrick Lencioni, also really took off. I hate to use the word pivot, but we are trying some new things that we’re excited about. I haven’t been this engaged in 10 years.